Why Give the Game Away? – an Interview with Foley

Collaborating as an artist isn’t easy: the energy we often bring to a project often relies on the maintaining of a personal fantasy or vision. Of seeing a thing, however dimly or brightly, in your mind’s eye and using its variable radiance as a guide in your construction. When the light brightens, we feel alive and energized, willing to pour more and more of ourselves into the thing we are making. When it dims, we feel lost, unsure of what we are doing, shameful in the prior optimism we once expressed. And on the cycle goes until we reach some point of exhaustion or completion and decide the thing is done.

This is all standard to the creation of anything but it also gets much more complicated when there begin to be multiple lights flickering around a project. We can feel our vision is being overpowered and overshadowed, and this might make us respond in any number of ways depending on how mature and calm we’re feeling that day. And these responses will create other responses; things will ripple and reverberate and soon the whole enterprise and expression might be in jeopardy.

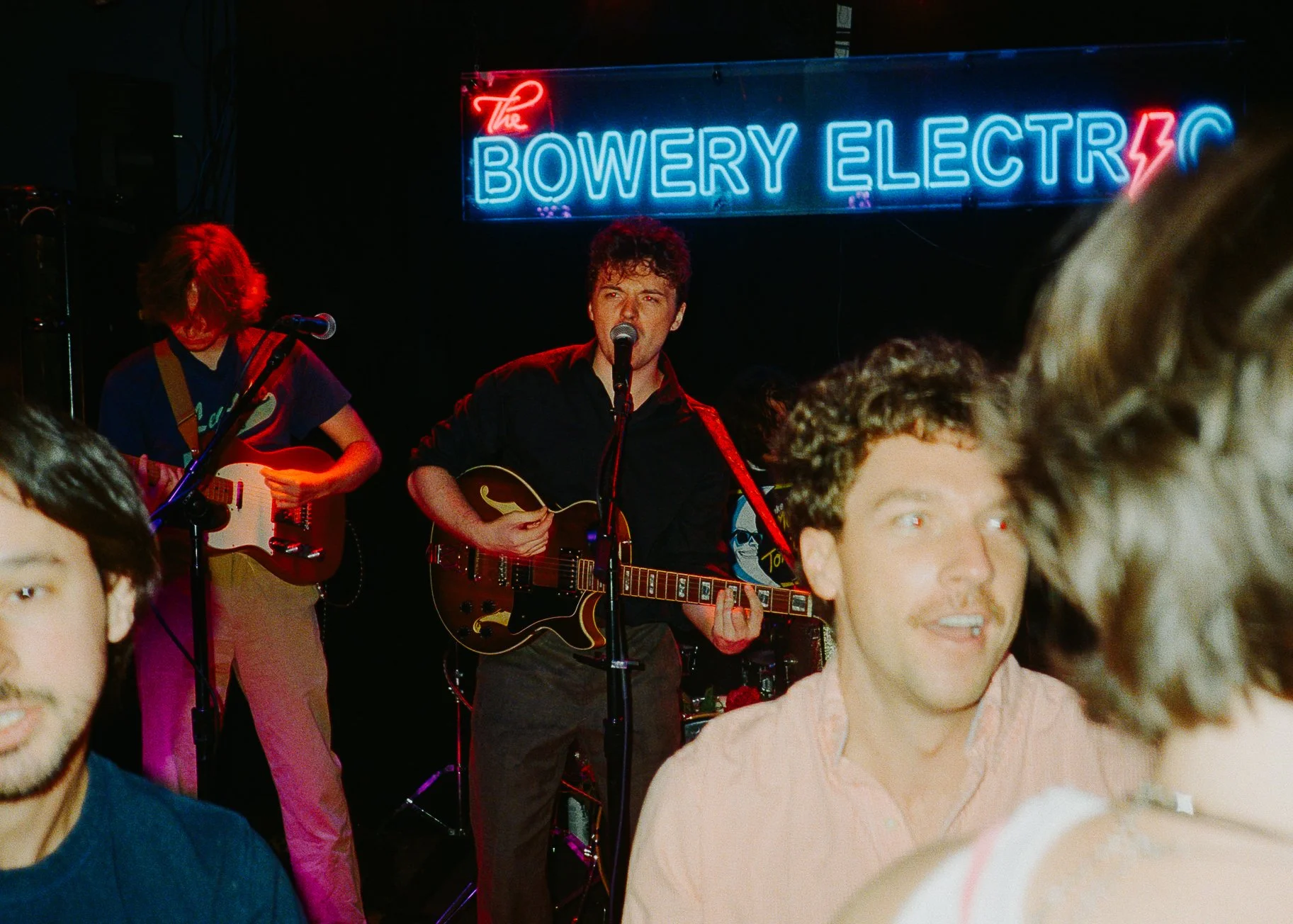

I sat down with the Brooklyn-based band Foley to talk about their newest album The Joke Turns Sad, song writing, as well as idea of collaborating in general. Talking with them has the feeling of being at a dinner table with a family you are visiting from out of town: they often interrupt each other, disagree, and retell the same stories differently. At first it felt like a great clashing of energies but the longer I spoke with them I realized this all a part of what made their music sound the way it did: by wasting very little energy on worrying about overstepping and focusing as much as possible on bringing forth each of their individual visions.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Good place to start, how long’s the band been together? How’d it start? What’s the origin story?

Eddie: We formed in 2017. Joe, Tom and I were at the same University (Hofstra) and it was just that freshman year of college energy where you’re kind of clinging onto each other. And we had a dorm room packed with guitarists and musicians all the time, singing Strokes covers and stuff, but the three of us would always be the last standing and songs sort of started emerging out of that.

From there the three of us started writing a bunch of music. It’s hard to call it a band really; it was more of a song-writing troupe. We would produce our own records and play whatever instrument. But in the past two years things have come together more. In 2021, Collin and Danny were added and that felt like a new starting point really. That’s when we started gigging and feeling more like a proper band.

Joe: And at the beginning we had this weird thing where I play guitar, Eddie plays guitar, and Tom plays bass, and we didn’t have a drummer. And it was like that for years. So one of us would sometimes be like, Well, I can play drums, and it would just sound like shit. Or we’d use a drum machine, or just not have a drummer and it was basically our Achilles heel. I knew Collin because we went to high school together and played in other bands together, so when we all finally converged in New York in 2021 it was this feeling of, finally, a chance to make the band into a real band.

Eddie: Although we recently found out Collin didn’t know he was actually in the band until very recently. I think he thought he was like a hired gun and no one actually asked him, Hey, do you want to join the band?

Collin: Yeah, I remember I was super tentative when talking about things like, This is the structure of this song, or, Why don’t we take this in that direction? because I thought I was basically just a member of the live act and that was only going to last however long. Then we had this whole hash-out conversation where they said, No, you’ve actually been in the band this whole time.

Collin mentioned before we started that a lot of the vision of the band circles back to you, Eddie. As in you’re the frontman and write a lot of the songs and maybe play captain for how things move forward. There are so many different elements at play in each song that I’d be interested to hear what the dynamic is like in terms of bringing forth a vision and trying to shape it with the group?

Eddie: It’s funny, when people are talking about musicianship and being in a band, you hear this idea of serving the song. I think maybe song is the wrong word there. I think it’s more accurate to say you’re trying to serve the whole musical expression. As a songwriter of the band I really think about that. How am I shaping the overall musical expression?

I write hundreds of songs. I’m writing songs constantly. And there’s this thing I’ll feel on certain songs where I’ll just know that it feels like a Foley song. A lot of that has to do with the taste of everyone else in the band. Their tastes filter out a lot of stuff that isn’t necessarily bad but isn’t necessarily us. So, it feels weird to take ownership of anything because without their taste as buffers or reflections of ideas, those songs wouldn’t exist. There’s just something mysterious that happens when you’re working alongside other people’s preferences. You’ll show something and sometimes you’ll have to be like, Alright, next idea I guess. And after a couple cycles of that you start to figure out what’ll perk people’s ears up.

Also important to note is that Tom and Joe both write for the band as well. So it’s not all me.

Less introspective question: Where does the name Foley come from?

Eddie: It’s a terrible name.

Danny: We were like, What if we had the least searchable band name possible?

Joe: Or, What if we took the last name of a more famous singer?

Tom: So it was something we thought about for awhile. We formed pretty organically in college and there were a few other people we’d been playing with for a few months and it just took us renting out a foley studio––we were all film students at the time, and I guess none of us really followed through with that––but we rented out a foley studio at school, and were just like, why not Foley?

Nice. Wait, what’s a foley studio?

Joe: Foley art is like in movies where you add a sound afterward. Like if you had footsteps in a movie but you didn’t record footsteps you’d record it later in a foley studio. And the person who does that whole process is called a foley artist.

Eddie: So, we would lie to get the space rented and say we were doing foley art and we were just recording our early demos.

Tom: Yeah the best mic we could find to record––

Eddie: It was a good film mic. It could capture sound really objectively but without any warmth or character. So our early demos have this sound of, say, a Tiny Desk concert or something where sound just doesn’t have much texture to it, which is because we were using film mics.

So everyone was a film student?

Eddie: Everyone but Collin.

Collin: Yeah I was a political science guy.

Eddie: Collin was gonna be a lawyer.

Collin: Yeah.

Let’s talk about the album that just came out: The Joke Turns Sad. Another interesting title. Where’s that come from? Any kind of driving force behind the album?

Joe: The Joke Turns Sad can ultimately be credited to Collin. Maybe it was just me that was thinking this, but I could have sworn the album was going to be called Songs of Foley. Because our last album was called Songs of the Lyrebird. We were trying to make an album that sounded more like we thought we sounded. Because we’d made two albums that weren’t necessarily folk rocky-y, and we thought what if we made an album that actually sounds like the way we think we sound. And I think it does do that. It does sound the way we think we sound.

And so I was like, well what about Songs of Foley? And Collin was like, that is a horrible title for the album. So we may have had two or three sessions when we were spitting out random phrases and eventually we arrived at The Joke Turns Sad.

Eddie: It was really frustrating because once you land on a name the album will really crystallize around it, and that’s a very exciting experience. Historically it had been pretty easy to come up with titles. It would be so obvious, you just say some phrase and it’s like yeah, that’s the title.

But that never happened. We sat around for hours just trying to come up with an album name and it never came. I’ve never done that. And so we were rehearsing for the album release pretty religiously, still no album name, and we were so beat, and I was like alright, let’s just take a day to refresh. Then we came back a day later and Joe was like, I think I got it: The Joke Turns Sad. And we’re all like, tentative, but yeah I think that’s it.

And ultimately I really love the name. Especially with the cover image of the lamb next to it. I couldn’t even really say what I like about it. It’s really mysterious but I just think it sounds great.

Throughout the album there is this dichotomy the name seems to allude to or express pretty well, I think. There’s often a rather upbeat and warm or frankly cheerful sound but a lot of the writing in the song feels quite sad. Like the song “Richard” does this pretty well. The surrounding sound is this joyful, playful thing but the lyrics are very much about longing or some kind of loss. Is that something you all think about, pairing these two contrasting elements?

Eddie: I don’t think it’s that calculated, but there are certainly techniques and tricks you can do to really layer sadness into songs. A lot of minor chords or certain words. Words like bones or lungs and strings and stuff like that. There are just a lot of ways to trigger the audience to think, Hey, this is gonna be a sad one.

But I think if you allow emotional complexity to come through sort of organically, so the music can sound however it is, then how you feel about it can be more up to you as a listener. I wanted these songs to be really open. So you could lean into them in whatever fashion you wanted to.

I was thinking about this as a writer. When you’re putting together a project, sometimes a scene, or a moment, or a chapter will arise, that you eventually realize is this type of key moment within the project. Like without that moment, whatever it is, the piece doesn’t really feel the same or complete. I was wondering if there was a song on the album that felt similar to you? And, as a group, if there was any kind of consensus?

Danny: There’s this moment that happens twice in “Pastor’s Daughter” where it goes from this really tense dissonance that begins with the lyrics “It’s way too easy,” and there’s this great unsureness that eventually breaks free into the “loving you” where it’s very pretty and we’re all together again. Like everything is broken up for a moment and then comes back into being aligned.

That, to me, as a band I feel like we tapped into exactly this sort of form to function. Like what Eddie was writing about, we all made that seen.

Collin: I was gonna say “Pastor’s Daughter” as well. Not to dwell on the album name, but I feel “Pastors Daughter,” lyrically and sonically walks this razor’s edge between things. Like it’s about someone who has a budding relationship with someone who has a terrible home life. And how can you look at the positive elements of an all-encompassing bad situation? And I feel like the music does a really good job of embodying this push and pull between despair and hope and happiness and grief. And I feel like The Joke Turns Sad, and the reason that name stood out to me when it was brought up––and why I had batted down so many album names prior; like Songs of Foley sounded like an aftermarket compilation album that you’d find in a record bin somewhere––

Joe: Alright man.

Collin: Sorry.

Eddie: Foley: All the Best

Collin: But it was like evocative––

Eddie: Foley Sings Foley.

Collin: But so the title we went with has this thing that sort of misses the mark. Or, doesn’t even miss the mark––hits the mark––but in a way that wasn’t intended. Like you tell a joke, and you’re trying to bring levity into a situation, but maybe you’re too prescient and actually land on something that is depressing or mournful. And I feel like “Pastor’s Daughter” embodies that really well.

Eddie: And not to belabor the point about the album name, but I think what Collin and Danny are both bringing up is this idea of tension into release, or release back into tension, and the sort of cycle of that. And I’ve noticed in prior albums, where usually I’ll be in charge of putting the song list in order which will create the narrative thrust of the album, and in writing everyone talks about the hero’s journey, or the Aristototillian rise and fall, and I’ve noticed that our past albums have kind of followed that, and something about that just felt so fucking phony. Because every story kind of follows that arc but I’ve just never experienced that kind of resolution of emotion, where everything is all figured out or tied up.

And what I really liked about this album was that it sort of starts out resolved and then complexifies as it goes on and becomes very unresolved by the end of the album. Like lyrically and musically there’s more tension and more dissonance. Especially lyrically. The resolution happens very early. Like the joke. And then it turns sad.

I wanted to talk about influence a little bit. You’re a chamber rock band right? How did you arrive at the sound you’re at right now? The really striking thing about this album I found is how grounded it is both sonically and conceptually. There’s a certain confidence to it and it feels like something that has been developed and tweaked a lot over time. Were there any guides in that development? Like a sound you’ve been aiming for?

Tom: From very early on I think we did a bad job of categorizing ourselves. When it was just the three of us at college we didn’t even know what we were. It wasn’t until there was this other student at Hofstra who was trying to be a music journalist and wanted to interview us. The interview never happened but in the process of trying to get it set up he asked us what genre we were, and Joe said Jazz band. And I was like what the fuck are you talking about?

Joe: It was sort of just top of the head. Like, yeah, um, Jazz.

Tom: But since then we’ve been calling ourselves a folk group but that doesn’t really sound right either.

Eddie: That’s why I like chamber rock. It’s descriptive in a way but also very undescriptive. It’s barely a box at all. Which is great.

Tom: But from very early on, and even now some, I felt like we really stuck out. Like in the Long Island DIY scene we didn’t really sound like the other people around. And our early recordings––Eddie how’d you describe them? Like what?

Eddie: Like not so good.

Tom: No but really there was this thing that stood out. Like an optimism. And they were all deeply personal stories. And that all contrasted with all the other artists we were doing gigs with.

Eddie: And that was kind of nice. It really set us apart. The scene in Long Island at that time was very confessional, and a little over-emotional. Sort of sing your deepest traumas into a microphone type of thing. And here we were, singing these very naive, bubblegum, folky pop songs that were sort of child-like in a way. It was good for us because we are able to feel different and I think the people listening appreciated it as a palette cleanser from these super intense acts. So we were really welcomed while also standing out a bit.

Joe: Going back to influences, I was thinking about it: it’s hard to describe because I don’t think we all have one source of influence. We all diverge at a certain level and go into our own things. And each one of our individual influences doesn’t take precedence but we are definitely all trying to make them present within the sound. And I think everyone is aware of that process and so maybe a little tentative to speak on what our influences are.

But there are some unifying ones. An early one is Leonard Cohen. That’s the first artist we all bonded over in college.

Eddie: And we bonded over the act of discovering him too which was cool. All three of us encountered him together. People refer to his song-writing as being like pistachio ice cream: like an acquired taste. And we were all interested in acquiring that taste. So the first few times we were listening we were all like wait, what’s going on here? He’s singing about monkeys and it’s all very confusing. What song is that?

Joe: “First We Take Manhattan.” Micheal Nau is another big influence.

Eddie: But Leonard Cohen is a good one because of the presentation of his music as well. Like how much dignity his songs have. He was in this pop world that was very youth-oriented but he was doing something that has as much poetic integrity as great poets or novelists. Bringing that dignity to such a youthful scene we found impressive. Like he would follow Jimi Hendrix at folk festivals and would win over the crowd and that’s sort of insane.

But yeah, Micheal Nau has really good sounding records. Sonically that’s our great white whale.

Joe: We reached out to the guy that mixed Micheal Nau and the Mighty Thread. We didn’t get to work with him because he was too expensive, but, like, one day.

Maybe you can get him For The Joke Turns Sadder.

Eddie: Or The Sad Turns Joker.

So how has this type of music been received in the New York scene? I feel like the stuff I hear a lot right now is very punk-y and a bit more abrasive. There feels like there is a trend toward distortion and complication, and to make something that is both lyrically clear and sonically clean and at times bright feels like it has to stand out a bit.

Eddie: Yeah it does feel that way. Like what Tom mentioned about us in the Long Island scene. How we were doing something very different. It feels that way still. But we’re used to it and I kind of like it. I like feeling apart from the scene a bit.

I had a conversation with someone after a show the other day and they were like no one in New York is making music like this right now, and I sort of thought it was a dig. Like, What are you doing? No one is doing that. And so I was sort of embarrassedly like yeah we’re fighting an uphill battle.

And he was like, I think you are, but I think you’re winning. And that felt really good obviously.

But the question is interesting given that we’ve been playing a lot more live since releasing the album. Our albums are a little quieter and calmer but our live shows are taking on this Vaudevillian sideshow aspect to them that no one has really expected. But, you’re right, when you’re in the live setting, at New York city clubs, it becomes really hard to resist putting on a crazier show. We’ve become, what’s the word?

Danny: We’ve become more theatrical.

Eddie: We’ve become more theatrical for sure.

The relation between recording and performing is always interesting to hear about. And how different those worlds can be. How they can clash: how you need to prioritize one at the cost of the other at times. It seems like you’re a band that takes a lot of pride in their recorded work; is performing taxing? Do you see catering to a live audience and the liveliness it requires coming back to influence your recorded stuff in any fashion? Are you all making some discoveries performing right now?

Collin: I can’t really speak to the era before I joined too much, but I feel like when Danny and I joined this past album was nearly half-done. The concepts were there, the artistic direction was clear, so I feel like for that period I didn’t feel like I was pulling the band in any particular direction. Going from a band with no drums to a band with drums and then Danny on the keyboard, it felt just sort of supplementary to the sound at that moment. But I feel like now that the album is out and we’re starting to strike new ground and trying to come up with new ideas, the drums are pulling the band a little. Toward something, I don’t know, maybe loud isn’t the word.

Danny: Ehh.

Collin: Okay, yeah, maybe loud actually just is the word.

Eddie: We’re rocking more.

Joe: Yeah I was thinking the same thing. Collin, you bring your influence in through the drums, which, not to generalize, gives a rock feeling. That’s on the album too. Like we could have found just some dude in a beanie, and he could have played all the songs, and it would have just sounded like a folk rock record. Not that it doesn’t sound like a folk rock record––

Eddie: Guys in beanies. You go to a coffee shop, they’re a dime a dozen. Pull ‘em out like a dixie cup and another one just comes right out.

Joe: But people have said that before about Collin. To his credit he can’t just leave well enough alone. So there’s a lot of influence on the album as well. Whatever part he’s given he’ll have to try to innovate. He’ll try to find a beat that not everyone is using.

Collin: Sometimes to a fault maybe.

There seems like there’s a desire at the core of the band that’s become clear both through your music and talking with you all. And I think the best way to describe it is trying to find cohesion through disparate elements without sacrificing the value of each individual element. Eddie, as the front man, how have you managed to accomplish that?

Eddie: There’s very little encouragement that I have to do. If you’re a solo musician and you’re directing the experience with a very precise point of view that’s great but as a solo musician I don’t. I think the band has a very clear point of view that’s carved over our relationships.

I’ve tried to make solo projects and I really can’t. All the energy ends up getting diffused. As a writer I need an assignment. And writing for this band is work that provides a narrowing lens that I think allows me to be productive. So it feels like that’s my only responsibility really: writing and focusing on writing.

Tom: I can attest to that too. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a moment of panic in your eyes when the band starts to move in a direction that might be opposed to your original direction. Every song and project that has come out of your head and we’ve worked on as a group has always felt like a very collaborative process in building that sound. And I think that’s why our sound works and why we enjoy playing together.

Eddie: That’s not to say that friction doesn’t happen. It does and we get into arguments about stupid things but it’s like throwing a bunch of rocks into a tumbler and letting them collide until they all come out very smooth. It’s never about ego when we argue––someone asserting dominance over everyone––but still in conflict the person with the right idea ends up being the loudest. We’re all very serious about making this the best it can be, and conflict comes out of that, but it’s always conflict for the greater good I think.

Danny: I think it’s actually a great amount of conflict. But it’s productive. And it shows in the music: if we ever find ourselves stuck between multiple ideas we end up just trying all of them and the best one typically wins out. But that requires everyone to stand up for their ideas.

I’m interested in the shared film background you guys have in relation to this idea of collaboration. Film being probably one of the most collaborative art forms there is, in which you have to wrangle a thousand different elements and people in order to create a singular vision or even just a small little moment within a film. Do you think about that relationship at all?

Danny: I wouldn’t say I think about it too terribly much. But in the sense that filmmaking is storytelling and Eddie, Tom, and Joe are all great storytellers I see the relationship. Like every little thing or image is sacred within their songs. And I know that’s just what imagery is, but the care they put into it reminds me of filmmaking.

Eddie: I like the attitude I’ve found on film sets I’ve been on, though I’m not that involved in film anymore. But you’re right: you’re working on a sort of moving ship with a bunch of timelines and restraints and if you’re not in sync the whole thing falls apart.

Danny: The film set is typically a bit more top-down though. The famous thing that everyone always says about film sets is that they’re little dictatorships. Where I think we’re a little more collaborative than that. Equals.

Collin: I feel like working on a collaborative music project has been a lot more enjoyable than working on films was. I just remember feeling really bogged down when working on student films and writing music for Foley became this great relief because the outcome was just so much faster. That was one of the reasons I didn’t really follow through on a career in film: because every little idea you wanted to move forward with had to be so meticulously planned and music is just so much more instantaneous. There’s so much more spontaneity. So much more accidental discoveries.

Danny: And not that these things can’t happen in film but I think they happen much more often in music. Those happy accidents. Like the song is already written when we get to the stage but the way we decide to play it is gonna be different every night. And oftentimes we even go out of our way to make that happen.

Eddie: In terms of the visual relationship, I think a lot of bands leave a lot on the table when it comes to the visual elements of their work. It’s obviously an audio medium but there are so many visual cues you can give both on stage and in your album. But nowadays with social media and all that it’s hard to tell a band they should be focusing on their visuals because what they think you’re talking about is getting like a brand consultant or something, but that’s not what I’m saying. So maybe it’s just helpful that a lot of us have a film backgrounds because we’re all just thinking about the visual presentation of the music and the group to begin with.

Eddie, do you think lyrically you find yourself to be a visual writer? I can think of a few lyrics off the top of my head that are almost like William Carlos Williams in their intimacy and precision. Do you think you stand apart from other songwriters you’ve heard in this regard?

Eddie: I’d almost want to field that to someone else honestly. Everything lyrically that I do I feel like I’m the last to find out. I mean it’s all very intentional but it has so much to do with preoccupations that are just in there. There’s a lot of imagery on the album for sure. But I think the art of lyricism is all images. I don’t think I’m aberrant in that way. Like if you’re not singing about images, what’s left?

Collin: I don’t know if I totally agree with you, Eddie. I think you can give yourself some flowers here. Because even before I was a member of the band the biting lyrics of some of the earlier tracks were something I found incredibly evocative. Invocation and evocation in music is important for me––it makes me feel like I’m experiencing something. And I don’t know if all lyrics are visual. Some of them are. But some are just human emotions. Raw emotions. And that can be cool and very direct but there is a certain inimitable quality to your lyricism that is built upon crafting a story in a certain way.

Eddie: I think what people think about when they describe imagery is specificity. Like a very specific detail is very important in storytelling. There’s this moment in Anna Karenina where the line is like “She played the piano, and she played it so loud and so good, that across the village the man in slippers carrying a loaf of bread turned his head.” Just giving the man slippers and letting him carry a loaf of bread paints the whole village for you. You only need those two details and then you have the whole place. Specificity is the most important element to the image I think. I’ve been trying to write short stories even and the first impulse is to provide a lot of details when describing a place, but you just never need that. Two or three specific ones do everything you need. And I guess I’ve begun to do that in my songwriting as well.

I think this specificity we’re talking about is very interesting in relation to the bigger ideas within the album. I feel like there’s this pursuit of a realness that’s very distinct. A reality of experience. Like I can’t tell you in a sentence what my childhood was like but if I describe what the cast I had to wear on my arm in the third grade smelled like, that’ll somehow get you closer to knowing my childhood more than anything I could ever explain. And I also think that can be at the heart of great lyric writing. Presenting the whole through the partial and incredibly specific.

Eddie: And that’s kind of how memory works, right? Like you remember one or two memories that contain the whole thing. Like a cup upside down, that had a couple drops in it that spilled onto the coffee table. And for whatever reason that was summer of third grade for you. And if you saw it again it would bring it all back.

Maybe that’s just how brains work. You save energy by just containing everything within a few specific capsules.

Danny: That’s what I was gonna say. Not to take it too far but our everyday perception is built like this. Like our sight, that is our mind filling in so many blanks. You can only take in so much at a time and you have to focus on a few key things around you to make sense of the whole.

Collin: I think that I kind of come to that when I talk to Ed about what his songs mean. Almost to the point where it’s been frustrating in the past. I’ll explain my interpretation of a song to him and instead of being like no, this is what I meant, he’ll go, hmm, yeah I guess it is that way. And that openness is one of my favorite things about your writing. Even from the first moment he’ll show us a song it just feels like he’s putting down a piece of paper down on the table and all the rest, the arrangement and production, everything else that goes into creating what the song means are to be determined after the lyrics have been written. So that openness remains throughout the process.

Eddie: I just think you do a real disservice to people if you just walk them through the whole thing. It’s insulting. But songs that will let you inhabit them, those are songs you can actually have a connection with.

But I learned a lot of this through trial and error and I also learned it from Joe and Tom who write songs that are hauntingly impressionistic. Like I remember when we first started making music together I would feel like such a chump. After classes we’d always be playing and all their lyrics would be so mysterious and have all this room for duplicity and mine did not. Mine would just be like a series of events. And I like that stuff, and we have some songs like that, but learning how to give more breadth and space in the song is stuff I picked up from Joe and Tom.

I think that’s a huge point that took me some time to learn as a writer: trusting your audience and the idea of insulting them by giving them too much. And it’s very refreshing to hear lyrics that allow enough space for you to step inside them.

Collin: Maybe that’s the biggest similarity we have to film. Of course Eddie’s lyrics are visual, but you never want to give the game away. You don’t want to just outright say what you’re singing about because that loses its allure. And everyone wants to feel like they can navigate a movie. Or a song. That they can ascribe their own idiosyncrasies within their own interpretation.

Tom: Maybe you can relate to that as an interviewer. Like the worst question you can ask someone is where do they get their ideas from.

Eddie: You should probably cross that one out.

Tom: But yeah just to echo what they were saying, why give the game away?

Eddie: Show don’t tell. Which is a film axiom as well.

So album out. How’s it feeling? Sometimes when I finish something major I go through a bit of a depression. Like maybe the things I was making art out of I wasn’t actually allowing myself to feel until the process is all the way over. How’s it feel to have this thing out there finally?

Eddie: So much of what we like about the creative process is that it’s sustaining. It really is sustaining to have something to work on. And I have friends that have been working on albums for years and years that might not ever come out because of that personal need to be sustained. And I have that pathology too, I think. I need something to be working on. Painting the walls on the dollhouse forever. And with music, where all the deadlines are self imposed, the good news is you can work on it forever, and the bad news is that you can work on it forever. But for that reason putting something out can feel terrible.

It’s funny, when people think of someone writing like a very sad song, they imagine someone sitting at their desk weeping or whatever. But honestly when I’m writing stuff like that there’s this great excitement to it. There’s this pursuit. You’re onto something good. Like the song “The Brightest Hideaway” had that feeling. When I was writing it I was just so excited and felt like the fox was in the bush and I was trying to catch it. And I was tweaking it and making it open enough to the point that it felt impersonal, but when I was going to record it, the song is in second person speaking to someone who passed away and I just had this moment where I was like, “Oh shit, I mean this.” And I had to take another month to finish it.

So you’re right, in a way you’re making a commodity: something that others can take away and use as their own. But there’s a tremendous amount of vulnerability involved which you can lose sight of once in a while.

And so with the album out maybe there’s not really an elation of, “Thank god it’s done.” But rather a relief to be shutting the door on some of that stuff. Not having to work on something that’s a manifestation of your grief or pain or whatever. That’s not an immediate feeling. There’s the initial pride in just being able to show people this thing that we made. But later is the feeling of being able to shut the door on that stuff.

Photography by Jack Pompe. More of his work can be found at jackpompe.com